Friends,

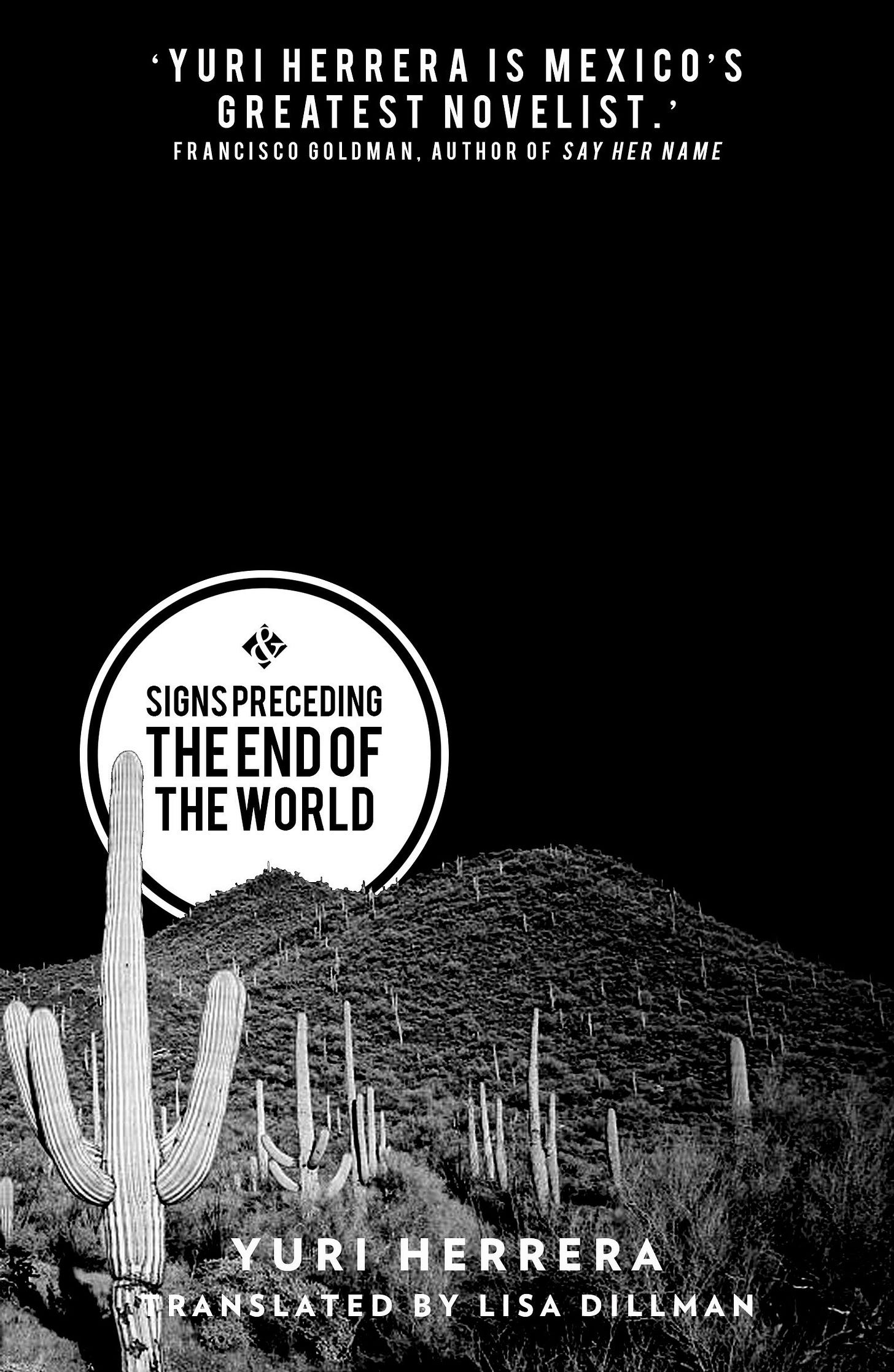

Happy New Year! As we prepare for the Age of Trump Part Two, a dystopian cross-over event that will take over the airwaves for the next four years, I’ve identified your next politically-engaged book club read. Whether that book club is entirely hypothetical or all-too-real, check out Mexican writer Yuri Herrera’s Signs Preceding the End of the World.

At 128-pages, Signs is a trim, fast-moving dream of a story. Hardly the shape of the kind of novel we’re used to in the US1. It tells the story of Makina, a switchboard operator in a small Mexican village, who is sent north across the Rio Grande to bring her brother home.

For your book club discussion, you might focus on Herrera’s use of mythic motifs (the coyote who helps Makina cross into the US is transformed into a kind of Virgil, the Rio Grande is the river Styx, etc.) as well as his slang use of the word verse, which is absolutely central to the novel.

Pair Signs with Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West for a discussion about the limitations of popular discourse around migration.

Or, if you want a deep dive into Herrera’s corpus, pick up Three Novels, a collection of, well, three of Herrera’s novels (251 pp.).

Included in the collection is Signs Preceding the End of the World; Kingdom Cons, about a songwriter in the Mexican underworld, but written in a chivalric mode; and The Transmigration of Bodies, a who-dunnit of sorts set during a pandemic and which would be a keenly observed Covid-era novel except that it was written in 2013:

Vicky came to give him a kiss and, right as she was about to, turned to one side and sneezed into her elbow.

Maybe one day people wouldn’t even remember when everyone had started doing it like that, instead of covering their noses with their hands. It takes a serious scare for some gestures to take hold but then they end up like scars that seem to have been there all along. Maybe they themselves would one day be nothing but someone’s scar, nameless, no epitaph, just a line on the skin.

Because like everything, this too would pass, and the world would act innocent for a while, until it scared them shitless once more.

Your friend in reading,

Evan

Becca’s Pick of the Month

Becca learned about an Italy she wasn’t familiar with in “The Priest Who Helps Women in the Mob Escape,” a New Yorker article from September.

“One interesting tidbit I learned,” Becca says, “was that if you change your name in Italy an announcement gets posted on a church in your hometown or something. That’s, like, the law that your name change has to be announced. So, its really hard to change your identity when you’re trying to escape the mafia.”

“You might have to fact check me on that,” she cautions.

Globally, it’s worth reminding ourselves, the constraint of the 300-page novel we’re familiar with in the Anglo world doesn’t exist. In India, novels can be long, baggy affairs. (A few months ago my good friend Dinidu Kurunanayake moderated a discussion with author Shehan Karunatilaka at Elon University, who talked about having to rewrite his Booker Prize-winning novel, The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida, for his American publisher. ) Throughout Latin America, shorter, linguistically experimental work is more common.

So sorry. One more dissertation because I can’t help myself: We in the Anglo world tend to forget that the formal and linguistic experimentation that characterized Modernism, which to English-language readers (and American university students) evokes the dour visages of T.S. Eliot or Ezra Pound, emerged as much from Latin America as it did from Paris. Nicaraguan poet Ruben Dario coined the term Modernismo in the 1880s to refer to the work he and other Latin writers were doing. Of course, this work wasn’t entirely Latin American either. It was influenced by all sorts of European avant-garde-isms of the late 19th century as well as by the anti-colonial politics and indigenous storytelling of Latin America. By the time Joyce and Eliot and Woolf were writing, there was already a robust cross-Atlantic pipeline of influence between Europe and Latin America. Literature is, and has always been, a global affair. While modernism in the Anglo world seems to have collapsed into post modern vapidity under the unbearable weight of unchecked market capitalism, it appears to have survived in Latin America. And so writers like Herrera are still possible.