Folks,

I get it.

Some people don’t care for Michael Chabon.

This was the sentiment of my Structure of Fiction class at Greensboro, when Craig Nova had my graduate cohort, 80% female, read Wonder Boys, a novel ostensibly about male geniuses and their herculean struggles to create art.

To make matters worse, he then had us watch the film.

Let me say this now, in case your only experience with Chabon’s work comes from the 2000 Michael Douglas/Tobey Maguire/Katie Holmes film: I assure you that the novel is much more self-aware and critical than the film would suggest.

So, some people don’t care for Chabon. He doesn’t do it for them, you know. His prose is indulgent. He over-relies on the simile. Etcetera.

But this month, feeling very bleh about how my writing was going, it was to Chabon I turned.

Because the thing about me and Chabon is, well, I really like him.

I think the following description of a country parson’s automobile from The Final Solution: A Story of Detection, encapsulates both what I find wonderful and what some find disagreeable about his work:

In fine weather, and driven by a man as sober as the tenor of his profession demanded, the Panicker vehicle, small, Belgian, ancient, ill-used by the son of its current owner and retaining few of its original constituent parts, was difficult to govern. Its tiny windscreen and broken left headlamp lent it a squinting, groping aspect, like that of a drowning sinner seeking an allegorical lifeline. Its steering mechanism, as was perhaps fitting, relied to a large degree on the steady application of prayer. Its breaks, though it was blasphemy to say, may have lain beyond the help of even divine intercession.

Is it a lot? Sure. Would you be forgiven for finding it a tad over-written? Of course. But for me, I read that paragraph and I think, “Man, Chabon was having a riot when he wrote that.” And that’s the sort of energy I like to feel when I’m reading.

The Final Solution: A Story of Detection (2004) is a trim detective novel set in England sometime after the allied invasion of Normandy, during the Second World War. It follows a certain unnamed-but-famous pipe-smoking, tweed-adorned ratiocinator (wink wink) who, retired to the English countryside, decrepit, and nearly senile, takes on one final case: to find a mute Jewish boy’s missing parrot.

Published three years before The Yiddish Policemen’s Union (2007, my personal favorite of Chabon’s novels), The Final Solution offers a sort of preview to many of the potboiler elements (and I use the term “potboiler” in the more colloquial sense to refer to, generally, a novel - a procedural thriller - driven by plot) that are so expertly executed in that much denser novel.

I find these sorts of “intermediate” books fascinating. I talked briefly last month about the way Dan Chaon’s Await Your Reply (2009) seemed, in certain ways, like it was preparing the ground for Ill Will (2017). In a similar vein, Jeffrey Eugenides’ short story “The Oracular Vulva” (1999), published in the nearly decade-long interval between his first and second novels, is clearly grappling with many of the same themes (sex, genetics, cultural taboos) that we later discovered would structure the magnificent Middlesex (2002).

Sometimes, I think writers are conscious when producing work of this nature—like a painter working through lesser studies in preparation for a much more intensive/extensive masterpiece. The Final Solution and “The Oracular Vulva” feel of this type to me: shorter, less labor-intensive works that anticipate the more “mature” novels they precede.

Other times, as I imagine was the case with Await Your Reply, a work only “feels” this way ex post facto. What’s actually happened is that the novelist, having encountered and attempted to exhaust a theme, discovers only after they’ve finished that they have more to say. In this way, a previous novel “ends up” being a kind of springboard to the next one.

Or maybe I’m just naval gazing here. Have you noticed similar sorts of things during your own reading of a particular author or set of works? Or do you find the very idea of an “intermediate” work offensive? Let me know.

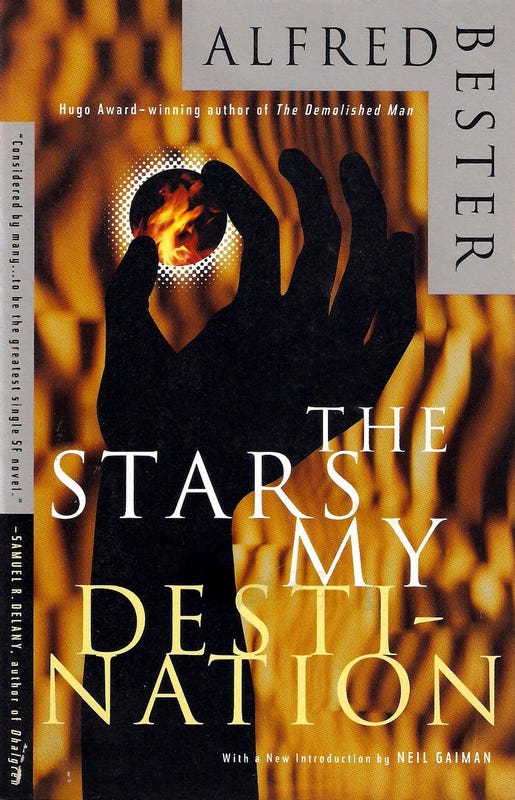

Briefly Mentioned: We Loved it All, Project X, The Stars My Destination

I managed my way through a few other books this month.

If “contemplative existential melancholy” is more your mood, check out Lydia Millet’s We Loved it All: A Memory of Life.

It’s a memoir—sort of—as well as a rumination on the complex of feelings that come with living in an age of widespread and catastrophic environmental damage. You might learn few new words to add to your climate apocalypse lexicon, like endling (a term for the last of a species), solastalgia (“the complex feeling of longing and distress caused by wide-scale environmental destruction”), and epoquetude (“the bittersweet comfort of a realization that, though the human species may not endure, some version of the natural world will live on after we’re gone”). An epoquetudinal worldview doesn’t provide any solace for me, but it’s a sentiment I’ve heard expressed by more than a few friends when the subject of climate change comes up (as it often does).

Or, why not troll your local Moms for Liberty [sic] and smuggle a few copies of Jim Shepard’s Project X into your middle school library.

Actually, it’s hard to say who the audience for Shepard’s 2004 novel was meant to be. It seems unequivocally Young Adult—first person present tense narration centered around two middle schoolers who are dealing with some stuff. And yet it also seems specifically designed to evade any public school library purchasing list. Too many fucks. Also, the perennially bullied protagonists spend the novel hatching revenge plans that include attempts to poison their school and, after one of the kids finds his father’s semi-automatic weapons…

Well, you see where that’s leading.

Whether Shepard’s novel did make its way into many middle schoolers’ hands (or school libraries) before the current censorship regime, I don’t know. It’s probably unlikely to now.

Which is probably a shame. Because it takes on a dark, difficult subject with humanity. And shouldn’t kids be learning that that’s the sort of thing they can turn to literature to find?

Lastly, because you’re the sort of person who subscribes to this substack, you’re also the sort of person who stays up late wondering, What if Alexandre Dumas had written science fiction?

Alfred Bester’s 1956 novel The Stars My Destination answers that question by reimagining The Count of Monte Cristo as a space opera.

Originally published in the UK as Tiger! Tiger!, Bester’s novel also draws on themes and imagery from William Blake.

Odd aside: If you ever thought the Green Lantern oath from DC comics sounded like something out of Blake’s Songs of Experience (1789), you’d be right. Bester, ever the Blake fan, wrote it.

“In brightest day, in blackest night, no evil shall escape my sight. Let those who worship evil's might beware my power… Green Lantern's light!”

The Stars My Destination was considered by some of the sf writers of the 60s, 70s and 80s to be the single greatest sf novel of all time. And hey, I liked it okay. But I’d say leave it for the die hard genre fans.

We keep saying goodbye to literary icons.

Paul Auster died April 30. Check out The New York Trilogy if you haven’t already.

The great Alice Munro passed away May 13. Read “Face.”

Chapeau!

(I’ve been watching a lot of professional cycling lately)

Evan

Becca’s Pick of the Month

Becca recommends “We’re Not So Different, You and I” from the May 13th issue of The New Yorker.

“It’s a four page short story. You know how some short stories end and you’re like, ‘What?’ That’s not this one. It was goofy and had me laughing out loud.”

P.S. Becca and I had a little party for our tenth anniversary.

Thanks to our great friends, who brought food, booze, ice cream, and good cheer.

Hi Evan!

Two quick things - one, I love the idea of an "intermediate work." Sometimes, as an early/zygote/ industry favorite term "emerging" writer, I worry over whether I will have enough ideas. That if I "spend" my One Good Idea on a short story, that it will have lost whatever life force it has, and can never be explore again. So I'd better get it right, because I get one shot at this! As you can imagine it is fairly limiting and unhelpful. It's great to think of writers I admire trying their hand and exploring themes long before the work they eventually became known for.

Second - Donette recommended We're Not So Different, You and I a few weeks back and I totally loved it!

Lu